#018 - Robot jobs

Sometimes AI is a better fit for that task. Emphasis on "sometimes" -- there are dragons beyond that sweet spot.

You're reading Complex Machinery, a newsletter about risk, AI, and related topics. (You can also subscribe to get this newsletter in your inbox.)

The robots can have it

(Many thanks to Vicky H for riffing with me on this segment.)

Salesforce is fully embracing the idea of AI as a way to replace human workers.

It's hardly a surprise, given that Salesforce [checks notes] wants to make money from selling AI tools. They're playing right into the desires of their target market – overly-hopeful execs who dream of swapping FTE headcount with cheap bots.

I'm not completely sold on this vision. Nor am I completely against it. My view is shaped by ideas that rarely come up in the AI Is Taking Jobs discourse:

- AI is a form of automation.

- Automation exists to replace human work.

- There's some work that humans don't want to do.

People overlook the first one because they want to believe AI is 🪄magic✨, and the term "automation" sounds too practical. The second is an open secret, addressed with hushed euphemisms like "disruption."

The third falls into the realm of "dull/repetitive/predictable," my indicator for work that is ripe for automation. (I've since learned that the military uses "dull/dirty/dangerous" in the same way.) This describes work that people would happily relinquish to a machine. The robot doesn't care that this is the eighty-sixth time today someone's asked about an item that is clearly out of stock. The robot doesn't risk veering into error out of boredom. And so on.

Some very non-AI automation offers an example: the self-service kiosk. McDonald's first tried this way back in 1999. I didn't encounter one till some years later, in a tourist-area take-away joint, and I immediately saw why these things had a bright future ahead. In short: not everyone is ready for a chit-chat. Some patrons were just too fried to talk to a cashier. Others possessed only a tourist-level grasp of the local language, ill-prepared for the dizzying array of options and upsells. Both groups found interacting with a touchscreen far less stressful than talking to another person.

(Ordering fast food doesn't seem like a big deal to you? Try doing it in a different language, in another country, and you'll see it for what it is: a skill that relies on knowledge of cultural context and special terminology. It's right up there with parsing stylized text or sussing out the incomplete grammar of signage, under the added pressure of doing it in real-time with an overworked cashier in front of you and a line growing behind. But I digress …)

The bonus was that the would-be cashier could focus on food prep and other work that was not amenable to self-service. That underscored a key point: we don't need people to ask a customer "what would you like?" and then tap it into their touchscreen.

Companies picked up on this in the early Dot-Com days, when they established self-service kiosks better known as websites. Booking a plane ticket? Don't call; go to the website. You've just moved and need to establish cable or utility service? Don't call; go to the website. Want to know what time this restaurant closes? You know the drill. Time to open that browser. Over time the self-service websites moved to mobile apps, grocery checkouts, and those "just walk out" Amazon stores.

We don't usually think of these tools as "automation." But when you decompose a business into processes – sequences of tasks – you see units of work that you can optimize based on who is assigned. Some of those tasks are currently performed by people doing robot-like work. Dull, repetitive, predictable. Begging to be automated away but we lack the machinery to do so. When new technology comes along, then, those tasks are up for grabs.

Getting a machine to do that work is a win for all involved – employer, employee, and customer.

Sort of. (Big asterisk here.)

Finding the sweet spot

To unpack that asterisk, let me add to the list I shared earlier:

- AI is a form of automation

- Automation exists to replace human work

- There's some work that people don't want to do

- There's some work that AI (currently) does not do well

Some tasks were practically built with future technology in mind. (For an extreme example, see last week's newsletter on the dawn of Wall Street's machine age.) Other tasks are far beyond the reach of present-day AI. (See: AI as your therapist.)

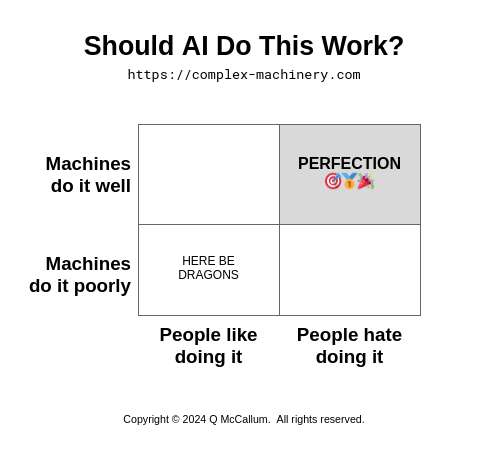

To spot opportunities for AI-based automation, look for the intersection of What People Don't Want To Do and What AI Actually Can Do. To put this in Consultant-Speak:

That upper-right quadrant? This is magic. Aim here for success.

(Please remember that this newsletter does not constitute professional advice.)

The lower-left? Madness. The realm of greedy misguided executives cramming AI into every possible human-shaped space. (Which, in turn, often stems from a lack of executive-level AI literacy. But that's a rant for another day.)

Installing an under-qualified worker is a bad idea, even if especially when that worker is a pile of code and linear algebra that has no idea when it's operating out of its depth. Doubly so when people are ready, willing, and able to perform. So if you want to load up on needless financial, operational, and reputational risk, the lower-left quadrant is for you.

In short: Find the places where AI works well. And leave some people around to handle the cases when the machines get stuck, or when a customer would prefer to speak with a human being.

OK?

OK.

Good talk.

Going rogue

Two weeks ago I pointed to olive oil as an example of This Looks Unrelated To AI But It Is In Fact Very Much Related. Same idea this time around, but it's about wifi.

The modern civilian world takes internet access for granted. Life is different in the military. Sometimes you have to go offline for a bit in the interests of national security. So it's kind of a big deal that some US Navy officers got caught running a rogue Starlink device on a ship.

Let's call this Shadow IT: Battleship Edition. It tells us a lot about the game of Shadow IT: AI that's playing out across the corporate world. Instead of sailors craving social media and cat pics, it's the employee who'd rather let ChatGPT write that ad copy. (As evidenced by the number of "ChatGPT does my job" articles from early 2023.) It's the department head who got tired of waiting for the internal dev team to build that feature, so they subscribed to an AI agent from an LLM vendor's marketplace.

Policies? Sure. You can draft all the No AI policies you want. Just remember that policies, like stop lights, are advisory mechanisms. You'll also need to root out noncompliance.

Detecting Starlink On A Ship was straightforward because even rogue wifi networks broadcast their presence. In this case, the (default) network name of "STINKY" was the giveaway. Catching Rogue AI In The Workplace will be tougher.

For text or code, everyone swears by some special tell for AI-generated content. The quality ranges from "this is iffy" to "Salem witch trials." The commercial AI-text-detection tools have also proven weak. But buyers want very badly to believe in them, so they keep shelling out cash. We'll soon have a cottage industry of detection tools for other venues. Expect them to be similarly long on claim and short on delivery.

Detecting other unauthorized AI will be a cat-and-mouse game. Internal audit teams will have to check company source code for calls to popular AI libraries or services. Maybe the CFO's office will subject discretionary spending to increased scrutiny, looking for charges to LLM vendors. (How soon till opportunists establish bland, innocuous-sounding companies to serve as pass-throughs? Definitely Not OpenAI, LLC is coming to a corporate card statement any day now.)

If things get bad enough, companies will adopt a rule common to trading floors: require key people to spend a couple of weeks disconnected from the office to see what breaks in their absence. If it works for catching rogue traders, it may uncover the department head who has gone around the policy.

Point being: I don't envy corporate legal, risk, and compliance officials right now. GenAI is too easy to access and too hard to find. Then again, there are too many legal question marks around the various services and their outputs to just sit back and let it happen.

L'enfer, c'est les robots

A lot of jokes are funny precisely because they describe something that hasn't actually happened. Like, say, chatting with an echo chamber of AI bots. That would be terrible, right?

The joke is now a reality, so you can find out for yourself. A group called SocialAI provides a social network where it's just you and a bunch of bots in conversation.

This is when you might tell me that social media is already a botfest. I would agree! Social AI leans into that idea by letting you pick the bots:

The types you pick will determine the flavor of the AI-generated chatter coming back at you. But Sayman says the app is also designed to learn and adapt to its user over time, based on the sorts of followers and content you’re engaging with.

Want cheerleaders and lovers to cling to your thoughts? Select “supporters,” “fans,” “cheerleaders,” and “charmers” and expect your most banal remarks to be overwhelmed with bottomless sycophancy. (“You look incredible!” “Oh darling, you look absolutely enchanting!” “Yasss, you look amazing!” etcetera, ad nauseam.)

(You know how judo involves using your opponent's momentum against them? I'm laying claim to "Product Judo™ ": the art of creating products by going with the momentum of something terrible.)

On the one hand, we could argue that Social AI lets you create your own reality. Right up there with the Pixel's new Add Me feature, which I covered a few weeks back. That strikes me as an unhealthy way to deal with the world.

On the other hand, maybe this is a good thing? Trolls and other attention-seekers would enjoy crafting an "online" experience to their precise measurements. They might even pay for it. Imagine if Twitter had done this, instead of trading chump change for blue checkmarks…? That $44B price tag might seem like a good idea after all.

Just a thought.

In other news …

- I've launched a fun project with longtime collaborator Scott Robbin. It's called Terrible.Food, and it's the place for you to share your stories of meals gone awry.

- Related to last week's newsletter, I forgot to share this video about the connections between poker and trading. (That YouTube video is a companion piece to the article, but doesn't require a subscription.) (WSJ)

- OpenAI wants to become a for-profit company. Wasn't it already one, effectively? This was such a non-surprise that it didn't merit its own segment in today's newsletter. (AP)

- According to one study, those AI-backed code assistants aren't doing much for developer productivity. (CIO)

- Dame Judi Dench and John Cena join the list of celebrities lending their voice to AI apps. (Der Spiegel 🇩🇪)

- Related to the jobs segment above, this op-ed emphasizes the value in the human-centric work that AI cannot do. (Le Monde 🇫🇷)

- Remember a few months ago, when Google's AI search assistant suggested that people eat rocks? Now it's serving up AI-generated images of mushrooms. Some of which are incorrect. Which is, y'know, kinda dangerous for people who want to know which mushrooms are safe to eat. (404 Media)