#035 - This time, it actually is different

GenAI breaks away from the pack. And not in a good way.

You're reading Complex Machinery, a newsletter about risk, AI, and related topics. (You can also subscribe to get this newsletter in your inbox.)

It's been a slow news week for AI, because a lot of … other things are going on in the world. Or maybe I'm just knee-deep in another writing project (more on that later) so I've missed the more exciting headlines.

Either way, I've had the mental space to reflect on the last couple of years of genAI. When I compare it to other waves of tech excitement, two opposing ideas come to mind:

- We've seen this movie before.

- Oh wait, this reboot of New Tech Thing has changed the script.

To the first point, the data space echoes the story arcs of the Dot-Com wave, cloud, and then mobile: "new tech comes along"; "people get excited"; "people later take it for granted as it becomes part of the everyday scenery." And in Structural Evolutions in Data, I noted how we're also watching reboots of the data story itself: predictive analytics, Big Data, data science, and ML/AI are all variations on the theme of "analyzing data for fun and profit."

To the second point, I think of the phrase "this time, it's different." It's usually trotted out to suspend disbelief, a way to explain why The Latest Hot Thing can't be held to the norms and rules of old. But genAI does indeed feel different. It aligns with its data siblings yet also pulls off in its own direction.

Given that, I wonder whether genAI is truly the next structural evolution of the data space. Or is it a different beast? Maybe a wolf in sheep's clothing?

I'll show you where genAI sticks to the script, and where it chooses its own path:

Same movie: Words have no meaning

Let's rewind fifteen years or so. One of the first things I noticed about the data field was the contrast between the firm quantitative methods it brought to bear and the very squishy terminology used to describe it all. You'd be hard-pressed to find clear, concrete, industry-standard definitions of key phrases.

Take "data science" as an example. Does it mean "building predictive models?" Maybe. But does linear regression fall under that tent? If so, why? And if not, why not? Oh, and since spreadsheets have regression toolkits, does the ability to use Excel make one a data scientist? When does predictive modeling no longer count as data science, but as machine learning?

The answer to that last question depends, in part, on when you ask – because in the early days, I could've sworn that ML was a pillar of data science. It's since struck out on its own, leaving data science to focus on … dashboards? I think?

Vendors translated the ambiguity into plausible deniability as they spray-painted "data science" across their products. Because, why not? If buyers wanted this thing called "data science" but couldn't tell you what it was, then they couldn't claim your product wasn't.

Job applicants followed a similar playbook in claiming to be data scientists. In response, many early practitioners adopted the loftier-sounding "machine learning engineer" title to differentiate themselves. There were days I felt people were spending more time picking titles than doing real work.

Fast-forward to the present and you get the same story with genAI. You might tell me that the definition of "generative AI" is pretty clear, but I'll ask you this: can a person claim genAI expertise if they've written code to create a synthetic dataset? Or if they've built Markov bots and restricted Boltzmann machines, yet have never touched an LLM? Can they make a similar claim if they've invoked popular AI chatbots but have never fine-tuned a model?

Apparently the "prompt engineer" job title has already faded. Which leads me to ask who, then, is building all of this genAI that every company is squeezing into their products? Unless they're just stretching the truth? (Hint: if you hate the UI/UX in the latest update, the app is actually using genAI.)

Same movie: Pushing ads

Pioneers like David Ogilvy did their part to improve quantitative rigor in the ad business, but it took early-day Big Data and data science to give advertising its numeric halo. What started as analyzing web traffic grew into the behemoth we call ad targeting. "Hell" met "Handbasket" and it's been downhill ever since.

This data-advertising friendship has continued through the present genAI wave – everything from synthetic images, to virtual models, to generated TV spots. Oh yes, and at least one genAI company is openly admitting that it wants to learn all about you so it can sell ads.

What I find strange is how much energy and effort go into something we consumers strongly dislike and have learned to tune out. Yet, I expect advertising and whatever-the-next-wave-of-the-data-field-is-called will continue to be BFFs.

(No, this didn't merit its own segment. But I wanted to call out intrusive, targeted advertising. So there.)

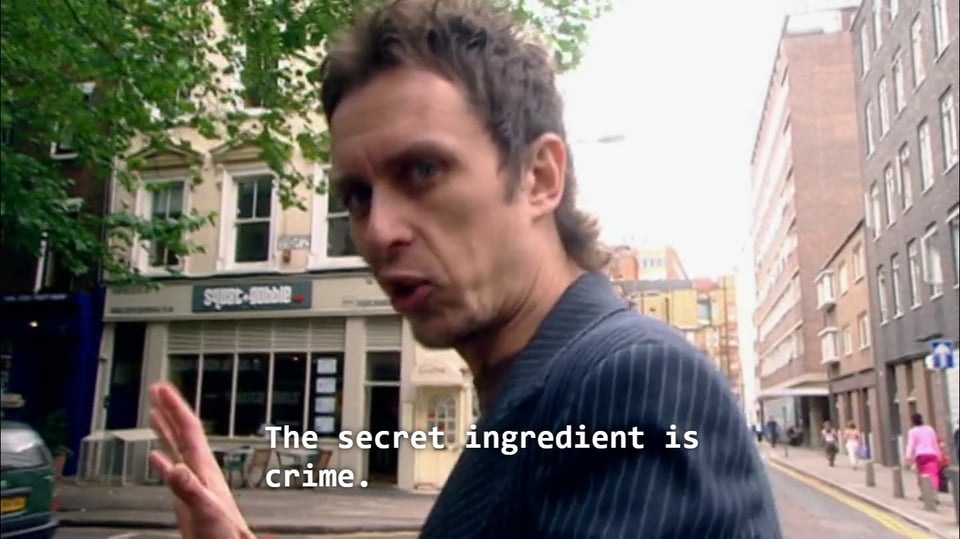

Veering off-script: Crime

Criminals tend to be early and eager adopters of new technology – consider the arc of phone scams, spam e-mails, hijacked websites, and rogue mobile apps. (Remember the iOS flashlight apps that would raid your phone's address book? Good times.) This crowd took a break when Big Data and data science arrived, though. The need to hire a bunch of data scientists probably put a damper on things.

Thanks to genAI's wide accessibility, they're making up for lost time. Thus far, the technology has been applied to deepfaked images, audio, and video; fake news sites on which to hang ads; and generated books to flood stores with titles on popular topics. Because when all it takes to make a book is to type "write one hundred pages on Topic XYZ," then selling even a few print-on-demand copies amounts to a profit.

(As someone who has written books for real, that actually sounds like a much better author experience. Hmm.)

Consider two recent cases of genAI fraud. In one, scammers have cloned respected Financial Times journalist Martin Wolf to pitch bogus investment advice through WhatsApp ads. In the other, scammers have created synthetic students to steal financial aid money.

I share these examples to drive home what I find so interesting about genAI crime: the perpetrators focus on what the technology can do right now. This sits in stark contrast to the rest of the genAI space, which is trying to get people amped up about what it might be able to achieve in the future. The uneven search for the killer use cases is papered over with excitement so we don't see the holes.

And that excitement, dear reader, leads us to where genAI very much breaks from the pack:

Rewriting the ending: A shaky enthusiasm

Compared to past tech waves, even past data arcs, genAI adoption is moving at high speeds with both individual consumers and corporate buyers.

All this enthusiasm feels much stronger than, say, early cloud adoption (which was mostly of interest to startup founders) or ecommerce (which took a while for both merchants and consumers to catch on). Even data science, as big as it would eventually become, took some time to warm up. In those days I met plenty of consulting prospects who felt they were getting "left behind" because they weren't adopting data science, and yet, even with that FOMO they continued to hold off. GenAI's adoption curve has taken a different, steeper shape.

Consumers dig genAI because they can coax the chatbots into doing their work for them. Executives want the same thing, just on a larger scale: they are in love with the idea of replacing half of their org chart with AI models. (To be fair, some execs see genAI bots as kindred spirits.) Recently, Spotify's Tobias Lütke joined the list of CEOs demanding their company cram genAI into every available crevice. And I'm sure nothing will go wrong there. Not a thing.

Buyers' excitement isn't the only thing that separates genAI from the rest of the data space. There's also something going on with the sellers.

Yes, genAI sellers and their cheerleaders have an economic incentive to grow market share. But there's a wrinkle. Have you noticed how many genAI proclamations are expressed in the (hazy, distant) future tense?

As I noted back in newsletter #19:

AI vendors keep getting tripped up on their Fake It Till You Make It routines, so they've changed tactics. They're moving away from concrete promises for today, and – taking a page from the cult playbook – declaring future dates for when things will pay off. "It's gonna be amazing in just a couple more years. You will be rewarded for your belief. Trust me. And also, pay me." This gives them extra time to turn their bold-yet-empty proclamations into something real. Or to wriggle out of the promises if things don't pan out.

(You know how cults always find some excuse when the big date passes without fanfare? With AI, they'll just rename the field and start over. Again. You heard it here first.)

And that was in October. Today, we have these claims of AI agents handling IT security (someday), to humans all becoming virtual bosses of these AI bots (one of these days), to people ditching apps because the robots will do all of the talking amongst themselves (eventually). Since they can't sell us on what genAI can definitely do today, they push what it might provide down the road. Maybe.

Each new offering is a distraction from the previous one's failure to deliver: from chatbots to search summaries, from search summaries to agents. As frothy as previous data arcs have been, we can argue that Big Data, data science, and ML/AI all actually did something and had concrete use cases. When applied properly, businesses could see real ROI.

By comparison, genAI has been racking up debt, pretending to be useful while trying to find out what it's good for. Selling genAI has become – and perhaps always was – a game of excitement, not utility.

I am hesitant to call genAI a bubble – technically, I can't do that till it's over – but the misallocation of currency and human capital, in the name of trend-chasing, is a warning sign. Doubly so when you see how the people who stand to make the most from genAI are fueling the very trend from which they will profit. They only have two cards to play – money and vibes – and with each round that hand gets weaker.

So if you'll indulge me, I'll close out by adapting my favorite scene from Andor:

Andor: Listen to me: they can't get genAI to catch up to the hype they've been pushing. And they know it. They're afraid. Right now, they're afraid.

Kino Loy: Afraid of what??

Andor: They've torched billions of dollars to puff up an AI dream! What would you call that?

Kino Loy: I'd call that power.

Andor: Power? Power doesn't panic. Their fanboys are about to find out that they're never getting AGI.

In other news …

- People continue to develop very … strong relationships with AI bots. (Le Monde 🇫🇷)

- That said, I doubt they'll fall in love with the boss's robot substitute. (Bloomberg)

- As more people turn to genAI services for search, marketers are adjusting their web presence to appear in results. (Les Echos 🇫🇷)

- Should you be polite when issuing prompts to an LLM? OpenAI says it costs more to do that. (Futurism)

- Yet more attorneys learn this lesson the hard way: genAI summaries are not a search substitute. (Ars Technica)

- Korea's webcomics (manhwa) artists size up AI's impact on their future. And not everyone is against it. (MIT Technology Review)

- ChatGPT has been groveling as of late. (Business Insider)